Why I'm giving up on NixOS

The good, the bad, and the ugly of NixOS; why I am going back to Arch.

TLDR

Why NixOS

I’m a uni student, and two years ago, I switched to NixOS because I wanted a system that was:

- Rock stable so I don’t have to worry about emergency repairs before an exam

- Easy to configure as I like to tinker with my settings a lot

- As minimal and as easy to understand as possible.

It’s not a stretch to say that I wanted what most developers need; a system I can trust that it would boot up and run. This is how I ended up on NixOS.

The basics

Nix works by defining the system within the main configuration.nix. For example, if I wanted to install firefox, instead of dealing with a package manager, you would instead write:

1

environment.systemPackages = [ pkgs.firefox ];

This extends to (almost) all settings that you could want, such as managing desktop environments, local users, and even the bootloader.

Because your system configuration exists in one file, it make it much easier to ‘transport’ it onto another machine with minimal changes. This is what makes NixOS declarative.

The good

NixOs meets all my personal requirements, and because it’s reproducible system we get some additional features:

- Managing multiple versions of the same program

- Stupid simple rollbacks

- Compatibility guarantees

I would say in general NixOS has everything that I love in a system, so I still will be running it for my homelab, just not as my daily driver.

So? What went wrong?

The bad

Configuring

My problems begin with what NixOS was designed to do. It’s a very subtle but recurring problem that can be shown with a relatively simple task: enabling bluetooth

1

hardware.bluetooth.enable = true;

As you can see, NixOS makes this incredibly easy. But lets think for a moment exactly how a newcomer may find this information. First we would google “how to enable bluetooth in NixOS”, then find the nix documentation on bluetooth, copy the line, paste it into our configuration, and rebuild the system. But wait a minute…

This is about the same workflow to enable bluetooth in arch!

as in, google “how to enable bluetooth in arch”, find the arch documentation, install bluetooth, and run the service.

Now don’t get me wrong, I fully understand why NixOS does this. NixOS is a declarative operating system, and I know that this way of doing things is offset with the benefits of reproducibility and portability.

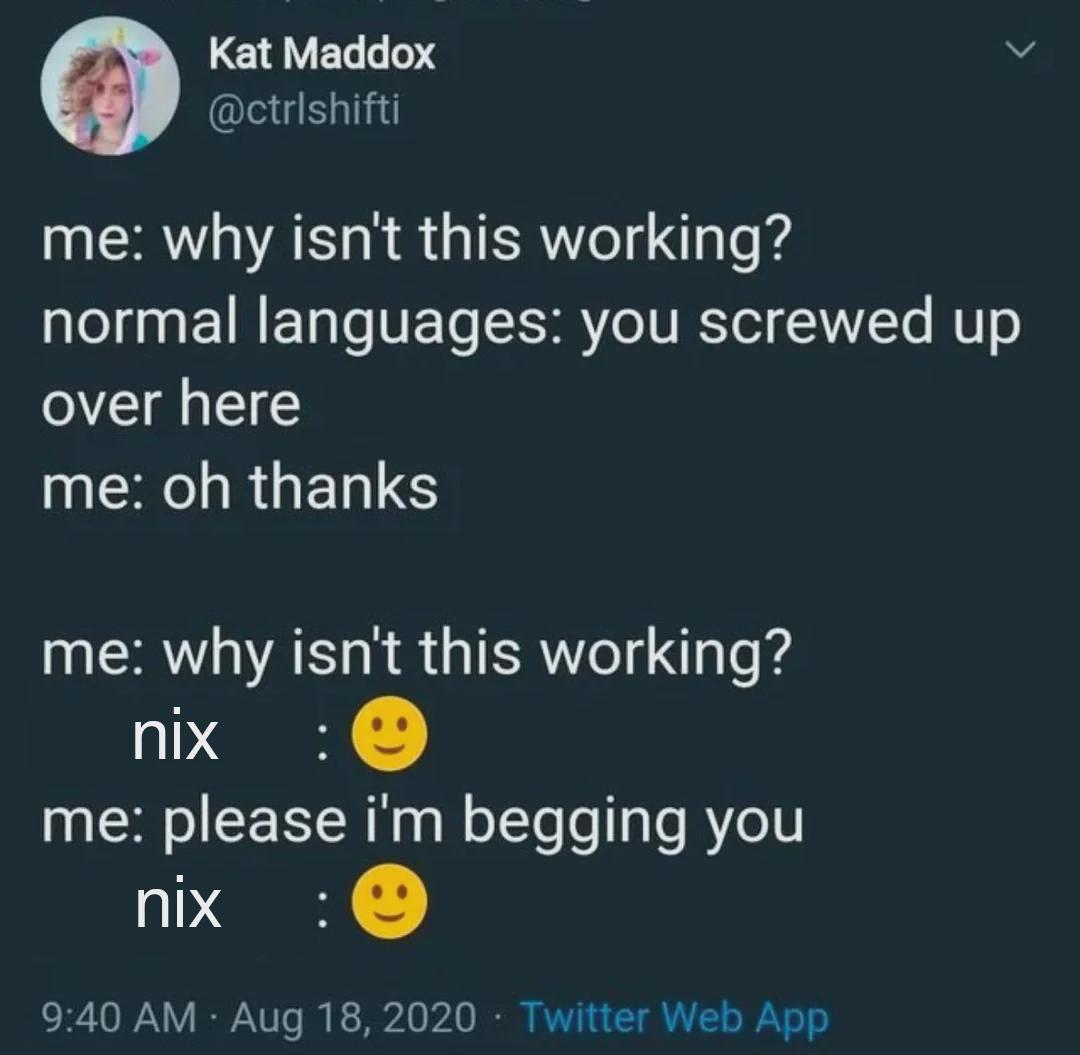

But as I used NixOS more and more, the pain of having to deal with the “nix way of things” unfortunately becomes more abhorrent.

Python

As a CS student, I need Python & PyTorch to be installed for my machine learning tasks. Normally, this would involve installing Python, then pip, then PyTorch with pip. Easy!

You would think that it should be at least somewhat similar NixOS, but it ends up screaming like a child at the thought of you installing a dependency from pip, because it must come from nix to be properly declarative.

It ends up looking like the following flake:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

{

description = "Python 3.9 development environment";

outputs = { self, nixpkgs }:

let

system = "x86_64-linux";

pkgs = import nixpkgs { inherit system; };

in {

devShells.${system}.default = pkgs.mkShell {

buildInputs = [

pkgs.ffmpeg

pkgs.python39

pkgs.python39Packages.pip

pkgs.python39Packages.numpy

pkgs.python39Packages.pytorch

pkgs.python39Packages.virtualenv

];

};

};

}

You would like that this is it, but when you run the flake, you realize that it is building PyTorch.

Why, for the love of God, am I building PyTorch after having to deal with the extra overhead of NixOS? This isn’t Gentoo! This is something that I need to configure for every single project! You would think that at least the performance should be theoretically better, but no, because NixOS by Python is built with the performance flags disabled, which in the worst case makes your Python code 30-40% slower!

Why?

Because it is the NixOS way.

Rust

If you build a rust project in NixOS, the compiled binary will by default reference /nix/store. This means that you are not able to run your linux binary on other linux machines. Let me repeat. You compile on linux, and it can’t run on linux. Something so fundamental and expected from every linux distribution is violated by default.

Then my journey continues like the thousands before me: I’ll deal with NixOS for a bit, writing my own flakes or shells, trying to find any documentation or existing implementations, then realize that it’s easier to build within a docker container anyways. Yup. I end up using debian.

Don’t even get me started with OpenSSL.

The ugly

Mouse acceleration

I’m not a gamer, but I like to play every now and again just as a form of relaxation from NixOS. While most people play with “linear” mouse movement (which just means that the speed of the mouse always matches the speed of the cursor), I prefer the more natural feeling of mouse acceleration because I grew up with it on windows.

But, for whatever reason, it’s simply broken for me; Libinput refuses to enable mouse acceleration. Ok, lets just brute force a solution then. Turns out, there are no kernel level modules that allow for custom mouse acceleration in NixOS! Want to make your own? Better learn more NixOS, because writing a kernel module isn’t hard enough as it is.

The benefit of enabling mouse acceleration is abysmal in comparison to the drawbacks of having to sell your soul to the NixOS ecosystem.

Vim

I wanted to learn vim as an alternative to my addiction to VSCode, but this is what ended up being the final straw that broke the camels back.

It starts with the biggest pain of NixOS and it’s only selling point, which is configuring programs that do not currently exist within the ecosystem. Nix’s solution to this is writing custom nix modules. However, what if you already have an existing configuration ecosystem such as neovim?

Neovim is doing it’s own thing, but NixOS wants everything to be done the “nix way”. This results in what can only be described as a mess. As an example, looking through the NixOS documentation on Vim, you can configure plugins with:

- A customRC command

- A extraConfig command

- Pathogen manager

- Vim-Plug manager

- BuildVimPlugin

- A DIY flake plugin

The best solution is to use someone else’s flake, but why do I need another layer on top of neovim? I only have my one PC that I will be using vim on so reproducibility on the operating system level is not needed, and lets be honest; Git is far better at version control than nix.

Even worse, when you do manage to install NVChad, you also need to install nerd fonts (declaratively of course), configure the terminal to use them, then realize you can’t because nix doesn’t install them to ~/.local/share/fonts and instead the documentation tells you to “just copy the necessary fonts” anyways??? AHHHH!!!

The more you use it, the more NixOS loves to get in the way and confuse you, only to waste your time and end up short.

Solutions?

The core problem that I have with nix is the same issue that it is trying to solve: dependency hell. I think nix does an amazing job at this, but I don’t think flakes are the solution that I was looking for - it’s almost comical that you have to learn a new language (it ain’t no python either) to manage their ecosystem which only adds to the confusion. I wish I could somehow just scoop off the best parts of NixOS and then it would be the last operating system I would install.

As a developer / university student, I simply don’t need my package manager to get in the way of configuring my system. Dealing with nix-shell and flakes on a daily basis is something I found myself not wanting to do. At the end of the day, the only people who would benefit from nix are other nix users.

Closing thoughts

I think for the problem is solves, it solves well.

Would I recommend NixOS to a friend? Absolutely not, let alone the average person, but I will admit it is an extremely unique experience that I wholeheartedly value. For the 1% that need NixOS, it is a perfectly fine operating system, but it’s grown to be incredibly distinct from any other linux distribution to the point where its getting in the way of what I want to do.